I just finished reading “Qualitative Interview Questions: Guidance for Novice Researchers” by Dr. Roseanne Roberts.1 While I was reading through the guide, it occurred to me that the qualitative interview is very similar to the patient interview in the first clinical encounter. In essence, clinicians become qualitative researchers every time we listen to our patients’ stories of what brought them into the clinic. Indeed, the qualitative process can help us become better at the patient interview, and improve our delivery of person-centered care. Let me explain the uncanny parallels!

But before we go further, I’d like to draw attention to the use of terms that may be confusing. Above, I used the term “qualitative interview” to refer to the qualitative research process. However, I also used the term “patient interview,” which refers to the “history” we take from a new patient in the first clinical encounter when trying to understand their diagnosis and to develop a plan of care. For simplicity and clarity moving forward in this blog, I will use the term “history-taking” to refer to the patient interview. However, I will continue to use the “qualitative interview” to refer to the information-gathering process in qualitative research.

The Goals of History-Taking and the Qualitative Interview

The qualitative interview is a “structured and purposeful conversation.”1 To quote Roberts1 further, “the goal is to acquire an understanding of the meaning and experience of the lived world from the perspective of the participant, communicated in their own words, and described in very specific detail to a researcher that is open and can set aside what they think and know about the experience being described.”

Similarly, when we, as clinicians, take a patient’s history, we try to find out what is bothering them, details of their signs and symptoms and how their condition affects their lives. We attempt to elicit their story about how the condition began, its evolution, and their emotions and knowledge about it in a non-judgmental, unbiased, and compassionate manner. Our goal is to gather as much information from the patient as possible to determine a diagnosis, and sometimes more importantly, understand how this is affecting the patient, so that we can determine a plan of care that is meaningful to the patient. We seek to understand the patient-as-person.

The Qualitative Interview and History-Taking Processes

Qualitative researchers believe that participants make sense of their world by filtering it through their experiences and their contexts. The interview itself provides research participants with an opportunity to reflect on their world and derive meaning based on context, their experiences, and what they know. Through these filters, they can then determine what is important to share with the researcher on the topic being investigated. This allows the researcher to gain valuable insight into the patient’s perspective.

When we, as clinicians, take a patient’s history, we also seek to understand what sense the patient makes of their condition through listening to their story. I have memories of professors in PT school saying that “the patient will tell you what’s wrong with them if you listen carefully,” and that “the history is the most important aspect in guiding you to a diagnosis and meaningful treatment plan.” It comes in the simplest, seemingly unimportant statements if we just let the patient talk. Just today a patient told me that he got some really bad news yesterday morning, and that afternoon his Ehlers-Danlos symptoms flared with all the anxiety and stress the situation created. This opened a door to ask more about the connection between his feelings and onset of symptoms and discuss possible mechanisms and triggers. In this way, taking a patient’s history can help patients and providers make sense of the patient’s situation together. Stilwell and Harman2 describe this as participatory sense-making.

Similarly, qualitative researchers understand that the research participant’s understanding of their situation can change during the interview as she (the participant) acquires more knowledge, or is able to process more during the interview. This is a form of participatory sense-making between interviewer and interviewee, and qualitative researchers have suggested that both parties work together to answer the research question within the interview.1 This is a form of constructionism where it is assumed that “knowledge is constructed in the interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee”1 such that one reality is co-created by both parties. It is an active process whereby participating in the interview triggers deeper thought and discussion about the topic with the goal of clarifying, rationalizing and understanding the issue in a meaningful way. This is in much the same way that my patient with EDS and I were able to make sense of his flare by further exploring the physiological link between stress and symptoms. We were constructionists, if you will, co-creating knowledge about his condition within the history-taking process. This allowed him to dive into deeper exploration of the nature of his pain.

Qualitative and History-Taking Questions

The qualitative interview process has a lot to teach us about how to effectively take a patient’s history. It can help us facilitate all that wonderful participatory sense-making. Indeed, there is considerable literature about the impact of the provider on the patient’s story, the patient’s beliefs, and the outcomes of care especially in the population of patients with back pain.3–6 Thus the healthcare provider should adopt a “qualitative attitude”1 and approach the history-taking process as a curious, active listener–listening to the patient’s story to gain an understanding of their condition, and what it means to them, rather than simply getting the patient to answer questions about their symptoms. So, let’s take a deeper look into the structure of the qualitative interview and the kinds of questions asked to see how we can apply them to history-taking in the clinical encounter.

In qualitative interviewing, the questions asked are of two kinds: thematic, which produces knowledge; and dynamic, which contributes to developing the relationship between the interviewer and interviewee.1 When we take a patient’s history, we are also seeking to gain knowledge by asking thematic questions, and rather importantly, we are attempting to develop the therapeutic alliance through dynamic questions. It is important to note that the questions need to elicit in-depth responses on the topic of interest, and therefore some practice may be needed to hone this skill of question-development on the fly, not only as a qualitative interviewer, but also as a clinician during the history-taking process with the patient.

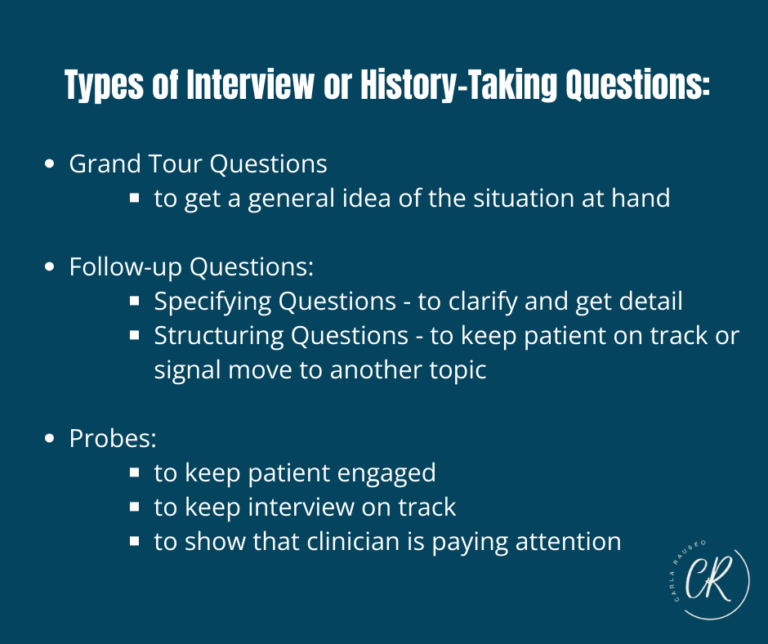

Roberts1 reviews the different kinds of questions in a qualitative interview and describes the purposes of each:

The grand tour questions:

The first type of question asked in a qualitative interview is the grand tour question. This question is very broad and seeks to elicit an overview of the issue at hand. This kind of question is very useful as an introduction into the history-taking process. As clinicians, we don’t usually know anything about the patient or their issue. The grand tour type question can serve to give us a “tour” of the problem for which the patient has come to us. Some grand tour questions can look like this:

- “Tell me the story of what bring you in”

- “Tell me about your back”

- “Walk me through how all this unfolded for you”

Follow-up Questions:

Active listening is critical during both the qualitative interview and the patient history-taking process. Good active listening allows us to develop effective follow up questions which qualitative researchers use to ascertain a more holistic perspective of the phenomenon under investigation. Through active listening, we can pick up on bodily reactions in the conversation and discern inconsistencies in the patient’s discourse. These can help us formulate follow up questions to seek further detail, clarification and meaning, as well as explore the emotional, cognitive and behavioural sides of the patient’s experience with the condition. Active listening also helps us to be flexible in our approach to the history-taking process and allows the interview to flow naturally. The follow up questions align with what the patient has communicated to us, and require us to be attentive, intuitive, and sensitive to what is being said, rather than only focused on collecting diagnostic information.

There are 2 kinds of follow up questions:

- Specifying questions. These are used to get more clarification and detail about a response form the interviewee, including emotions and thoughts, reactions to events, and to explore connections or interactions between aspects of the answer. Examples include:

- Can you describe this in more detail?

- Can you give me additional background on how your pain began?

- What else stands out to you that happened or was different around the time of the onset of your pain?

- Structuring questions are used to keep the interviewee on track or to signal movement to another topic.

- You mentioned earlier that you felt confused and frustrated…can you elaborate on what you mean by this?

- Is there anything else that is important for me to know about your experience?

There are no hard and fast rules about using follow up questions, what to ask, or how to ask them. They are meant to be used flexibly and should flow naturally to create a comfortable conversation that keeps the patient at ease. They should, however, seek to elicit meaning, context, associations, and causal links. They should address contradictions, clarify explanations and perspectives, and gain personal insights. For example, an elderly patient may say that she lives alone in a 2-storey house. A follow up question seeking to clarify or get more detail on her household mobility could be simply, “Tell me how you manage around the house and do the things you need to do.” From this, you may garner that she has a daughter who has installed a stair lift for her, so stairs are not an issue. However, she does have a small dog who jumps, and she’s worried that will make her fall, so she uses a walker for safety, but can cook and do simple chores once she has the walker. Note that the follow-up question is not a yes/no question. It is specific to the home environment and her ability to perform her ADL’s, however it is vague enough that she is able to give a lot of very useful details that can help determine a meaningful plan of care…that stairs are not her priority in her 2-storey home, but falling is a major concern!

Probes:

In the qualitative interview, probes are used to keep the interviewee engaged, to show that the researcher is paying attention, and to manage the flow of the interview. They are also used to maintain focus on the topic. They can be very useful in the patient history-taking process, and I’m pretty sure most of us use them unconsciously.

Probes can be non-verbal such as facial expressions, nods, gestures, and body posturing. They can also be verbal such as when we say “uh-huh,” “go on,” “oh my goodness! Tell me more!” and “can you give me an example?”1 These probes can facilitate thicker descriptions from the patient.

According to Roberts,1 probes can also be used to:

- Bring the interviewee back on track. Questions such as “you were telling me about what your doctor told you. Could you go back and tell me more about what he said?”

- Summarize and ensure that you understand what the patient says: “You said that you got into the accident on October 10th and the pain came on 2 days later, and it has been progressively worsening and is now moving down the back of your leg?” This also shows the patient that you’re following along closely as she speaks.

- Ask for clarification: “I don’t quite understand, can you explain in a bit more detail?”

- As prompts to elaborate: “Sounds like this was a very difficult time for you.”

- As a credibility check: “How exactly did that happen?”

Ordering Questions

In the qualitative interview, ordering questions is important because the correct flow of questioning can help us to build trust. In the history-taking process, we can use it similarly develop the therapeutic alliance, and decrease the threat of the clinical encounter, particularly for patients who have not had good experiences with healthcare. Good ordering of questions helps to create a safe space for the patient to share sensitive information, and creates a smoother interview, decreasing awkward moments.

Based on work by other authors, Roberts1 recommends that we order questions from easy to hard. Initial questions such as the grand tour should prompt general descriptions of the phenomenon or experience. We can then work up to the more sensitive questions that answer “why” or “how” once we have gained trust and placed the patient at ease. These would include questions that involve emotion and impact. Some examples may be:

“How has this impacted your ability to take care of your baby?”

“How do you feel about not being able to work?”

This ordering actually does work, and here’s a story from experience: I always like to find out my patient’s home situation, who they live with and what the household is like. I used to ask that question earlier in the history-taking process and found that patients would be very short and even vague with their answers. They would hesitate often, particularly adults who still lived with their parents, as they may have thought that I would judge them based on that answer. So, I started asking it later in the interview when I felt that patients were more at ease. I have found that at this later time, patients are much more amenable to sharing more personal information once I keep a non-judgmental approach.

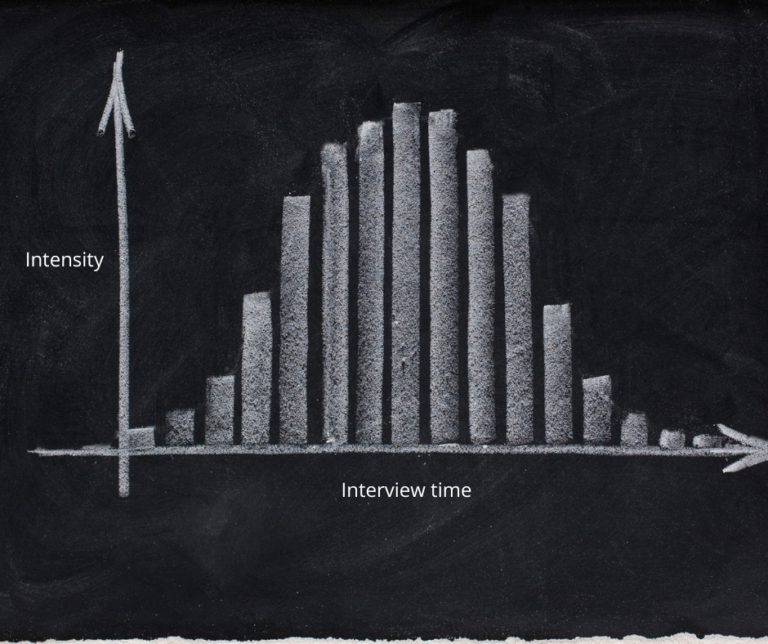

Debriefing

If we were to graph the intensity of the patient history-taking process, I believe that it should look like the normal distribution, an inverted U (sorry for the nerding out here! I swear that I don’t really like statistics!). At the beginning, you’re trying to create trust and develop rapport, so the questions asked should be simple, broad, and not very stressful…low intensity. As you progress to the middle of the process, more personal, distressing conversation may then take place as the patient shares more of her story…higher intensity. The end of the interview should return stress and anxiety levels to a lower level, and this is where debriefing comes in to lower the intensity.

Debriefing in qualitative research involves summarizing the insights gained in the interview, and asking the participant if she agrees with the summary. It can also entail offering the subject an opportunity to clarify or add to the information given in the summary, and time to discuss the experience of the interview, including concerns and future use of data are also part of the debriefing process.

Similarly, in the patient history-taking process, the patient should be debriefed. It’s important to summarize what the patient has told us, to show that we listened to her concerns, and offer her opportunity to add to that summary or to correct anything that may be wrongly interpreted. In this debriefing process we should also give the patient our assessment of the situation, help her to understand her condition, and explain a plan of care and prognosis. This can be a very involved conversation and we may not be afforded the luxury of spending a lot of time with our patients. Therefore, asking the patient what is the most important question that she would like answered in that initial encounter can allow us to prioritize. You can also let the patient know that you can continue the conversation at the next session and that you will be happy to answer the rest of her questions then. You can then end the interview with a little small talk or humor to continue to lower the patient’s level of anxiety.

Reflection

In qualitative research, reflection after the interview is a crucial process. It allows the researcher to reflect on what happened in the interview, to note if her biases influenced any part of the process, and to note any significant interactions or moments that may have occurred. This reflection helps with her interpretation of the information gained in the interview.

In the time-crunched world of healthcare, we often have little time to spend with our patients and may focus on certain aspects to the neglect of others. It is therefore very important to reflect on each patient encounter to determine what went well and what we should improve upon or address at the next patient visit. As in the qualitative interview, this reflective practice can help us interpret the information gained from the patient and chart a meaningful plan of care. In fact, there is support from the literature that reflection improves the competence and self-efficacy of physical therapists.7,8

In the reflection, you review the history-taking process in your head and assess the kinds of information you received, the patient’s affect, your reactions and behaviour and any outside forces that may have affected the interview. Was the information you garnered enough to make a good plan of care? Do you have a good handle on the life experience of this patient and how this disease impacts her life? Did you show empathy and validate the patient? Were you affected by any biases? If so, how did you handle them while with the patient? Did the interview flow well? Do you need to ask more questions of the patient? These are some of the kinds of reflective questions that can provide additional insight into your history-taking process. They can not only improve your skills as a clinician, but can help to give your patients an exceptional healthcare experience.

Recognition of Provider Influence

In that first patient encounter when we’re taking the patient history, we are essentially interviewing the patient about her condition. Just as interviewers qualitative research can influence the research participant, so too can we as clinicians influence our patients. In qualitative research the interviewer is viewed as an instrument that needs to be calibrated so that she does not “lead the interview” based on biases and predetermined goals and expectations, as this can affect the quality of the data received from the research participant.1,9 “The interview becomes a research instrument for interviewers, who need to learn to act receptively in order to affect as little as possible the interviewee’s reporting”1

Similarly, we as clinicians engage in participatory sense-making with our patients. We therefore have massive influence on not only what our patient tells us, but on how she make sense of her situation. Just think of the young female patient with low back pain (LBP) and a newborn baby whose healthcare provider tells her that the back is fragile and that she needs to protect the back by avoiding lifting. The narrative she plays in her head about her back can be very disabling to her as a mother who needs to lift and carry her baby. Compare this patient to another young mother with LBP who is encouraged by her HCP to continue her daily activities and receives reassurance that it is safe to move. Her quality of life and engagement in activity can look very different to the former patient.

Thus, we need to check our biases and assumptions, and be mindful of how we, as a human instrument, as the “doctor-as-person,” can impact what our patient tells us, and the narrative they create about their condition. This returns us full circle to the importance of active listening, asking the right kinds of questions in the most appropriate order, and always being mindful of how we are influencing our patient.

The patient history-taking process is a critical skill in person-centered care. It’s truly a skill that requires a lot of practice, errors, and reflection. It takes considerable time to develop. I think it should be taught early in healthcare education, rather than relying on internships to teach the brunt of these skills to our students. We also have a lot to learn from qualitative methods and skills, such as how to conduct a patient history! I hope to see more of it in our entry level programs.

References

- Roberts RE. Qualitative Interview Questions: Guidance for Novice Researchers. The Qualitative Report. 2020;25(9):3185-3203. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4640

- Stilwell P, Harman K. An enactive approach to pain: beyond the biopsychosocial model. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. 2019;18(4):637-665. doi:10.1007/s11097-019-09624-7

- Darlow B. Beliefs about back pain: The confluence of client, clinician and community. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2016;20(April):53-61. doi:10.1016/j.ijosm.2016.01.005

- Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Annals of Family Medicine. Published online 2013. doi:10.1370/afm.1518

- Darlow B, Dean S, Perry M, Mathieson F, Baxter GD, Dowell A. Easy to Harm, Hard to Heal: Patient Views About the Back. Spine. 2015;40(11):842-850. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000901

- Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, Hurley DA, Baxter GD, Dowell A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: A systematic review. Eur J Pain. Published online 2012:15.

- Chuan-Yuan C, Ying-Tai W, Ming-Hsia H, Jia-Te L. Reflective Learning in Physical Therapy Students: Related Factors and Facilitative Effects of a Short Introduction. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013;93:1362-1367. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.044

- Ebert JG, Anderson JR, Taylor LF. Enhancing Reflective Practice of Student Physical Therapists Through Video-Assisted Self and Peer-Assessment: A Pilot Study.

- Peredaryenko MS, Krauss SE. Calibrating the Human Instrument: Understanding the Interviewing Experience of Novice Qualitative Researchers. The Qualitative Report. 2013;18(43):1-17. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1449